Speed Score

A method for understanding when we need to take out time on a decision or move quickly

A method for understanding when we need to take out time on a decision or move quickly

This score is inspired by ideas presented in Annie Duke's book, How to Decide, and aims to combat heuristics and biases that tend to convince us to move fast when we should move slow or paralyzes decision-making altogether.

Heuristics: Mental shortcuts are hardwired and build over time that create the illusion that the correct choice is clear when we either don't have enough information or worse, the information we believe we have is bias.

Action Bias: To fuel moving forward without enough information, we tend to bias action over inaction.

Paralysis of choice: The more options we have, the harder it is to make a decision - even with decisions that are seemingly trivial.

Penalties and Payoffs: Out fears around negative outcomes and regret tend to overshadow upside. Understanding our bias to focus on risk over gains can help move forward with accepting and mitigating risk instead of allowing it to delay a decision.

The speed score is a tool that helps us quickly isolate decisions that we can make quickly versus decisions that need time - even if we think the decision is clear.

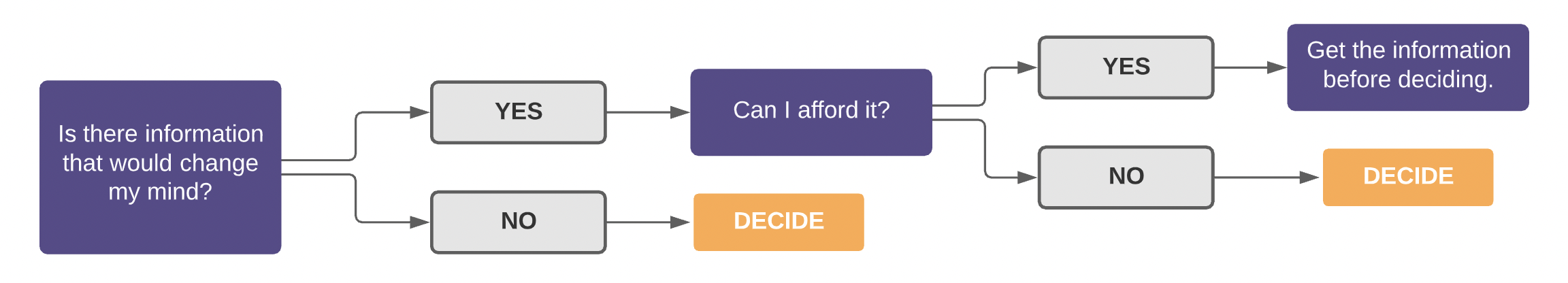

Annie Duke's method outlines a very simple question that can immediately segment our decisions, "Is there information that would change my mind?". Poking holes in our decision-making, often referred to a 'counter-thinking', is a powerful way to combat bias and check whether or not we're making a decision because we're confident in the information we have or because we're acting solely on intuition

Start by seeking enough information to challenge your thinking and gain confidence in the decision. If there is no information that will change your mind (even if you knew that information) or you the information is too costly to attain, then move fast.

Move fast if: There is no information that will change your mind (even if you knew that information) or you the information is too costly to attain

Move slow if: What you believe to be true about your assumptions could potentially be false, explore how you could gain confidence.

The terms 'one-way door' and 'two-way door' decisions were made popular at Amazon to describe whether or not a decision can be reverted. Just as it sounds, a one-way door decision is incredibly costly to backtrack (if backtracking is even an option) while a two-way door decision has a fallback (though the cost to revert may vary.

For two-way door decisions, it's helpful to map the 'penalty' for a wrong decision. We can ask "What if we're wrong?" and use an outcome tree to trace the possible negative outcomes and the estimated cost to revert them.

Keep in mind that these these types of decisions are contextual - a one-way door decision for a single team (like choosing a new hire) is often a two-way door decision for the organization that team is in. A new team member has massive implications on the team, but less so for the company as a whole.

Move fast if: A two-way door decision has low 'penalty' for being wrong. Utilize outcome trees to measure the cost of potentially negative outcomes.

Move slow if: Dealing with a one-way door decision

Decision boosters are tools to increase decision velocity. One of these tools is simply your intuition. Daniel Kahneman, a founding father of judgment and decision-making sciences, found that some of the highest velocity decision-making processing relied on intuition to make quick decisions, but with a very important caveat; this only works with informed intuition at the end, not the beginning of the process.

This leads to a very important note: Intuition only works in environments of extreme validity. An executive who has performed countless product launches will likely have better intuition when making go-to-market decisions, but intuition should only help us get past the goal line quicker, not be the basis for the decision.

Two additions to the speed score to boost velocity:

Repeating decisions: Identify decisions that repeat often and move even faster with those. These are great candidates for rapid experimentation. Examples would be implementing a new shopping cart flow to see a lift in conversions or changing product pricing.

Decision stacking: This is a helpful tool to help reduce risk and increase speed for slow, one-way door decisions. Break the decision down into smaller incremental decisions or 'validations' the help reduce risk or gain confidence, then resolve the low-impact decisions first. This pair well with assumption mapping.

Here's what it looks like to fold repeating decisions and decision stacking into your speed score:

Annie Duke, How to Decide. 2020

The Decision Lab, Heuristics, explained.

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow. 2011

Track the forces at work as your company absorbs a change after a decision

The DACI framework is a simple, yet effective way to quickly identify roles and responsibilities in a decision making process.

Why we often only make choices that are satisfactory, not optimal